About Pakhawaj

The Pakhawaj, also known as the Mridang, which is the generic Sanskrit term for a barrel-shaped drum, is regarded as the most ancient percussion instrument in North India and is considered the predecessor of all North Indian drums.

History

Mythology states that Lord Brahma himself created this divine instrument from the skin and blood of an evil demon. When Lord Shiva defeated Tripurasur, the demon with his trident, he began dancing his tandava. The earth began shaking and falling apart due to the lack of proper rhythm. To remedy the situation, Lord Brahma mixed the demon’s blood with the soil of Earth, utilized his skin, and instructed Lord Ganesh to play it, resulting in the creation of the Pakhawaj. In ancient times, sadhus (Hindu monks) employed the instrument as a supplementary instrument for chanting religious prayers to gods called shlokas. As a result of this ancient tradition, these religious poems continue to be utilized in Pakhawaj music.

Pakhawaj today

The Pakhawaj’s low, mellow tone and rich harmonics make it the perfect percussive accompaniment for pure, less heavily ornamented classical styles of Dhrupad music. In the 20th century, the rise of Khyal music coincided with the popularity of a new instrument, the Tabla, which resulted in the Pakhawaj becoming a distinct art form in India. Nonetheless, due to its sophisticated rhythmic patterns and pure depth of meditative sound, the Pakhawaj is regaining popularity today as both an accompanying and a solo instrument. It was also the primary percussion accompaniment for Kathak and Odissi dance, as well as a temple genre of song known as haveli sangeet.

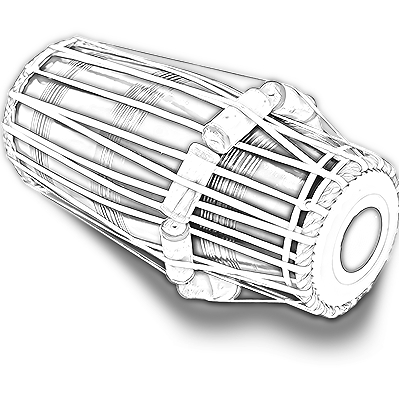

Originally made of clay, the Pakhawaj is now primarily constructed of wood, typically black sheesham wood, with two parchment heads, each of which is tuned to a distinct pitch. The heads are three-layered skins made from goat skin or shagreen, with black paste applied to the right head known as Syahi. The Syahi is made from rice, coal, and iron powder and is carefully applied to the skin in a circular motion, necessitating precision and extensive practice from instrument makers. To tune it, tension is applied to the straps (baddhi) by knocking the wooden side-blocks (gattas) into place and holding the skin (puddi). A tuning hammer is employed to alter the pitch on the treble side of the drum. The left side of the drum is tuned by applying dough made of flour (atta) and water.